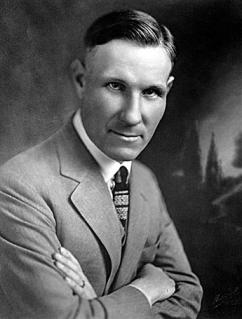

In this first article in an occasional series on the history of United Parcel Service and workers’ resistance to Big Brown, examines the company’s founder James E. Casey–the so-called “Package King”–whose personality and polices still shape UPS to this very day.

UPS founder James Casey

UPS founder James Casey

“Deft fingers wrapping thousands of bundles…What a treat! Ah, packages!”

— James E. Casey

THERE ARE few other things in life that get a UPS supervisor or manager more excited than the sight of thousands of packages or Next Day Air envelopes careening down the myriad of belts crisscrossing the company’s sorting and distribution centers–known as “hubs” in the company lingo–across the world.

Their eyes widen and their breath quickens. You can almost see the dollars signs popping up in their eyes, like old-fashioned cash registers, as each package passes by. These packages of every shape and size are like little nuggets of gold, from which the UPS fortune is made.

They are more important than the physical and mental health of the workers who sort, load, unload, repair, clerk and deliver them. UPS includes in its corporate “mission” statement noble-sounding words like “service” and “integrity”–as if the company is most concerned with promoting the common good. But Big Brown is, after all, first and foremost in the business of making money off of its workers.

The obsession with packages goes right back to the company’s hallowed founder, James E. Casey. “Casey once told me that he had never drunk a glass of milk in his life,” the head of a department store told a reporter for The New Yorker for a 1947 story, “and I thought for a minute, he might stop talking about those goddamn packages and tell me why he never drunk a glass of milk. But no! He went right into night loading operations in Chicago.” Clearly, Casey wasn’t much of a conversationalist.

On another occasion, Casey, while visiting a client’s store, dropped into the wrapping room and was reportedly ecstatic at the sight: “Casey’s eyes sparkled, and he began to twitch. ‘Deft fingers!’ he said. ‘Deft fingers wrapping thousands of bundles. Neatly tied. Neatly addressed! Stuffed with soft tissue paper! What a treat! Ah, packages!'”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

WHAT SPARKED the interest of The New Yorker about Jim Casey and UPS in this post-Second World War era? It appears to have been a messy, wildcat strike on the streets of Manhattan that shut down UPS operations for 51 days in the fall of 1946. (More on this later.)

Those were the days when UPS did home deliveries for New York City’s leading department stores, such as Lord & Taylor. Customers would buy their items, and the department store would package and wrap them, then hand them over to UPS for home delivery. The strike prevented New York’s middle- and upper-class shoppers from getting their goods, which seems to have the eye of the editors at the New Yorker.

Philip Hamburger–who would stay at the New Yorker for a total of six and a half decades–was assigned to go interview Casey and get a feel for the company that had become so indispensable to New York City’s retail businesses.

The company was already a third of a century old by this point. A 19-year-old Casey founded UPS in 1907 as a bicycle messenger service in Seattle. In 1913, it started to deliver packages, and over the next decade, the company spread down the West Coast.

By 1934, Casey was important enough to be featured in the “Talk of the Town” section of the New Yorker. The editors gave the story the distinctly condescending title of “Errand Boy.” It was a short article that acknowledged Casey had begun his career doing “errands,” but his business had changed considerably: “He’s sort of an errand king now, the head of the United Parcel Service, which delivers packages by the millions in this city and elsewhere.”

The article, by an unnamed author, picked up on company policies that struck many people then (and now) as military or even cult-like: “The employees are about as regimented a bunch of people as you’ve ever heard of. For his first few weeks, he is tutored in driving, delivery and courtesy. This involves a hundred and thirty-eight rules.”

The story goes on to mention a summer camp: “When business is slack, the unmarried deliveryman may spend their time at a camp in Connecticut which the company operates for them. Several hundred go there every year for a month or two.” What went on in these summer camps may be lost to history, but they were clearly about creating a private world, where employees were strongly encouraged to adopt the values of Jim Casey.

By the time Philip Hamburger interviewed Casey following the Second World War, Casey’s stature in New York had made a big leap forward. Reflecting this, he was bumped up to the “Profiles” section of The New Yorker, usually reserved for major figures of the business and political world.

Casey was no longer a new face in town–he was the head of a major business, and a growing one. Late in 1946, UPS delivered its one-billionth package. In 1947, it employed 2,800 people and operated 1,700 trucks in New York City alone. It was operating in 17 major cities across the U.S. and delivering 100 million packages a year.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

WHAT MAKES Hamburger’s profile of Casey so interesting seven decades later is that it gives an unvarnished look at the man, as opposed to the manufactured legend familiar to UPSers today. Casey comes across as an austere disciplinarian with a more than slightly loopy fascination with packages.

“Casey is a tall, spare man of 59, with high cheekbones and, most of the time, a rigidly detached expression,” reported Hamburger. He found Casey hard to interview, describing him as a “taciturn”–what most of us would call dour–who was reluctant to answer questions.

However, when reporter and interviewee moved from Casey’s fourth floor office at the old Manhattan hub on First Avenue to view the endlessly moving belts of the package sorting system below, Casey perked up. “He becomes animated in the presence of packages.” Hamburger described the “surf-like rumble of the parcels” filling the air–something that anybody who has spent any time in a UPS hub will recognize to this day.

“Casey’s life is devoted almost entirely to packages,” Hamburger reported, though this vocation was combined with a deliberate faux modesty about it all–“Anybody can deliver a package,” Casey told Hamburger. But Hamburger wasn’t buying the line–“He does not believe it,” the reporter wrote.

Hamburger picked up on the way Casey packaged UPS’s image, just like the neat and tidy packages his drivers picked up at fashionable New York department stores, and that so delighted Casey. “Over the years,” Hamburger wrote, “Casey has taken what might look like to outsiders like the simple job of handling and delivering packages and turned it into a semi-religious rite.”

A “simple job” is an overstatement, but “turning it into a semi-religious rite” is right on the money. Every aspect of the company image was carefully created, from the crisply pressed brown uniforms to the company slogan “Safe, Swift, Sure.” The mystique of the UPS driver was an important selling point–an incredulous Hamburger wrote that the drivers “are governed by a series of regulations that could be easily be mistaken for the house rules of a Tibetan monastery.”

Drivers had to carefully study–before hitting the road each day–illustrated cards that scolded them to: “Check and double check: Are your shoes shined? Is your hair cut? Are you clean-shaven? Are your hands clean? Is your uniform pressed?”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

IF THIS seems like an obnoxious way to treat grown adults, it didn’t seem to bother Casey, who made periodic visits to UPS hubs to enforce the rules, like a general inspecting his troops. “On one such visit,” according to Hamburger, “he stood by as a [hub] supervisor assembled a group of drivers and package sorters, and examined their shoe shines and haircuts.” He then declared, “The spokes of our wheel spell service,” and left the building.

Casey made workers jump through hoops to get hired. According to Hamburger:

Applicants for United Parcel Service jobs must, first of all, impress a personnel man with their neatness and courtesy. If they pass muster on those counts, they are subjected to intelligence tests. No one at United Parcel, least of all Casey, is searching for a genius-type deliveryman. The personnel department has discovered that high-scoring applicants are inclined to be temperamental and to mislay their bundles. Assuming that the results of an applicant’s test place him somewhere in the broad category between wizard and idiot, and that job is available, he is hired.

Hamburger’s snide comments aside, he does capture Casey’s search for the moldable personality he could shape into the proper driver. This molding process continued after work hours. “A man who gets a job at United Parcel finds that his education has just begun,” Hamburger writes. “The leisure hours of an employee are supposed to be crowded with self-improvement projects.”

Such projects included reading the UPS newsletter The Big Idea, which was filled with homilies to the UPS way of doing business, employee profiles and witticisms from Casey himself.

The UPS search for the perfect worker led to periodic rebellions against the military disciple and cult-like atmosphere at the heart of Casey’s policies. The company’s founder never tired of trying to “improve” his drivers. One of Casey’s more obsequious biographers, Gregg Niemann, in his 2007 book Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS, enthusiastically defends such policies with the statement, “UPSers turn out better than machines.”

Casey’s obsession with packages also never flagged. In one memorable scene in Hamburger’s article, he captured both Casey’s fascination and bigotries together:

Recently, he stood silent with a friend, watching thousands and thousands of packages. He was silent for several minutes. Then his face lighted up. He seemed exhilarated. “Packages for everybody!’ he exclaimed suddenly. “Packages for Chinatown–a difficult area. Drivers have trouble remembering who they left the package with–everybody looks alike! Packages for Harlem–hardly any charge accounts in Harlem! Packages for the West Side–democratic neighborhood. Give packages the kind of welcome packages deserve! Packages for Greenwich Village–very odd packages!

In the next installment of this series: How did the Teamsters penetrate this strange little fiefdom?