Tag Archives: UPS driver

UPS Drivers Who Avoid Accidents for 25 Years Get Arm Patch and Bomber Jacket

Chadd Bunker says his friends and relatives tell him he drives like an old man. Roll through a stop sign? He would never do that. Exceed the speed limit? Not on your life. He makes three right turns to avoid a left. He can be annoying.

But Mr. Bunker, who is only 48 years old, is no ordinary driver. He recently became one of the proud, lucky few to reach the delivery driver equivalent of Eagle Scout—the United Parcel Service Inc.’s Circle of Honor.

The award goes to those who manage to drive their big brown trucks without having an “avoidable” accident, for years and years. That isn’t easy since UPS considers nearly every kind of accident avoidable. A scratch on the truck while backing up, or a tree branch hitting the vehicle and breaking a mirror, they both count as accidents that might have been avoided.

Drivers who make it through 25 years are honored with a little ceremony, a patch on their sleeve documenting the number of accident-free years and the ultimate king-of-the-road status symbol: a bomber jacket.

UPS is driven by its safety culture. New drivers at the 107-year-old company are required to attend intensive, weeklong training courses, informally dubbed “Quaker boot camps” that emphasize ethics and safety.

It isn’t the only company to toot its horn for safe drivers. PepsiCo Inc.’s Frito-Lay honors its million-mile safe drivers at an annual awards gala at its headquarters in Plano, Texas. The achievement typically takes 12 years. Con-way Inc., in Ann Arbor, Mich., bestows a class ring on its two-million-milers, who also get an embroidered jacket and business cards. Waste Pro USA Inc., in Longwood, Fla., awards its garbage truck drivers $10,000 for three years of spotless work. Spotless has three components: a positive attitude, good attendance and no accidents. UPS-rival FedEx Corp. gives awards too, recognizing employees after each year of safe driving.

For UPS drivers, the road to glory is very hard. UPS drivers must memorize the company’s more than 600 mandatory “methods.” These include checking the mirrors every five to eight seconds, leaving precisely one full car length in front when stopping and honking the horn just so: two short friendly taps, no blasting.

There are all sorts of potential hazards. In Ketchikan, Alaska, for instance, Tom Fowler, 53, dodges black bears and deer on a regular basis. In the snow and ice, he parks, then pulls a sled of packages a quarter mile up narrow roads on steep, slick hillsides to avoid the possibility of a vehicle accident. He became the first Alaskan driver to make the circle of honor in January.

“When you’re out delivering, it’s not unusual to see bears, black bears. People do hit ’em,” Mr. Fowler said. It’s “a big crash if you hit a bear.”

About 1,500 were inducted into the circle in 2013, and a mere 7% of the 102,000 UPS drivers on the road are members.

Drivers agree the most impressive record belongs to Ronnie McKnight, who has driven safely for 46 years in New York City, dodging aggressive taxi drivers and parking precariously on a daily basis. Mr. McKnight, 71, learned to drive slowly on a tractor at age 11. Now, he says, his secret is “patience. Don’t be in any rush to do anything.”

Lately, UPS actually has been pushing its drivers to speed up, while still adhering to the rules. Thanks to the boom in e-commerce, drivers say they’re delivering more packages than ever on the same routes. Average daily package volume has grown 12% over the past five years, while the number of drivers has stayed roughly the same, according to the company. Some drivers complain privately that the company’s expectations for safety and efficiency can be contradictory. “The job can be done as efficiently as we’ve designed it, and safely, if you follow the methods,” says UPS spokesman Dan McMackin, who used to be a driver.

Tom Camp, 73, is the company record holder for 51 years of safe driving—in Michigan, of all places, a state snow- and icebound several months of the year. He has no plans to retire. “Every day is a challenge out there,” he says. “It takes your full concentration, all the time.”

Still, it’s all too easy to hit a bump in the road—or a chain-link fence. That’s what happened to Rui Sousa, a 49-year-old Providence, R.I., driver as he tried to turn around at the end of a dead-end street in 2003. He scratched his vehicle and wiped out a perfect 15-year, six-month-record. His heart sank.

“It’s hard to swallow when you go that many years and then, boom, there it all goes,” he said.

Luckily, UPS allows for detours. If a driver has an accident after five years of safe driving, the clock is set back by at least a year, but the previously accumulated years still count toward the final tally. Before five years, drivers go back to zero.

Mr. Sousa was set back by 18 months. He now takes extra care when backing up, often getting out of the vehicle to check whether he has enough space.

In October, after another 10 years of safe driving, he finally made it to 25 years. He now parks in a reserved front-row spot at his building. As part of the award ceremony, his brown jersey was retired to the rafters of the building, where it dangles as inspiration for younger drivers with a dozen others. He now has a new shirt with a small, round sleeve patch with the number 25 on it.

Drivers have a choice between a camel-hair blazer and a leather bomber jacket as their prize. Mr. Sousa chose the bomber jacket. “I wear it on special occasions,” he says. People “think it’s very cool.”

Jimmy Hoffa 1957

Texas Style

A man without a country

If you were going to suggest a cast for a reality show about life in the suburbs, you might pick Nick Ortega and his family. His house in Loveland is the stereotypic American dream: two-car garage, neatly trimmed lawn and family pictures in every corner of the living room. Downstairs, in the basement, you’ll find Ortega’s “man cave,” a couch facing a big screen TV, a foosball table and a couple of guitars from Ortega’s rock band days in the 1990s.

There are pictures of Ortega when he was a kid on a baseball team, and photos of his son’s team with Ortega standing to one side as coach.

Beyond this slice of Americana is the “living nightmare” that Ortega has yet to tell his neighbors about.

After more than four decades in Colorado, Ortega was shocked to learn that he’s not an American citizen, as his parents had always told him.

“I still wake up and can’t believe it,” he says.

He’s worked for decades in the United States without any problem. He’s filed income taxes since 1983. He has a driver’s license. He bought a house. For two decades he has lived with his common-law wife, a multigenerational U.S. citizen from Montana. Both of his children are citizens.

Ortega may have never found out he wasn’t a citizen if United Parcel Service, his employer of more than a decade, had not in 2010 run his name and the names of his coworkers through E-verify, the Department of Homeland Security’s internet-based system for determining whether employees are eligible to work in the United States. UPS told Ortega that his Social Security number identified him as someone born outside the country.

“‘That’s strange,’ I said,” says Ortega.

So began a frustrating and emotional journey where Ortega, now 47 years old, began to unravel family secrets that nobody had ever told him.

“My parents just never talked much about the past,” he says. “It was very difficult to get answers out of them.”

Eventually, he did. Ortega discovered that he was born in Mexico in November of 1966. That made him a year older than he’d always been told. He learned that he migrated from Chihuahua, Mexico to the United States with his mother and siblings in 1972 around the age of five. They traveled on a bus that was waved through a U.S. border checkpoint in El Paso. From there, the family traveled to Colorado to be with Ortega’s father, a Texas-born U.S. citizen from a family with a long tradition of farm laboring. Ortega has been in the United States ever since.

His upbringing in Greeley, Colo., was modest. His family was poor, working hard for subsistence wages. After he graduated from high school, Ortega did some construction as well as gigs with his rock band. He settled into a job at a rent-to-own store and later worked several years for a furniture sales ware house. One day, he set his sights on a job that would provide a more secure foundation for his family — driving a truck for UPS. He began as a seasonal driver, but worked constantly, punching the overtime clock every time his managers said there were extra hours to fill.

“I knew there were a lot of drivers who wanted to go full time, so I made myself stand out by working the hardest,” he says.

It paid off. He was hired as a regular driver with benefits, joined the Teamsters Union and over the years steadily inched his way up to a payday of about $90,000 a year. He shows a stack of honors he received from UPS, including nearly a decade of safe driving awards and honors for “Total Quality Service.”

When the news came that UPS was letting him go, Ortega was devastated.

“It was like my whole world was crumbling around me,” he says.

Only a handful of states require E-verify checks as mandatory for all employers. Colorado is not one of them. In Colorado, only contractors for the state and the city of Denver are required to undergo the checks that critics say may unfairly target workers and can be open to fraud. A Homeland Security Department study found that about half the undocumented workers checked by E-verify were deemed eligible for work.

The Teamsters Union Local 705 in the Chicago area chided UPS for using E-verify to check 340,000 workers around the time Ortega was let go. In the Chicago area, at least 280 employees, including possible U.S. citizens, were reportedly dismissed, according to a statement by the union.

UPS failed to return a request for comment by deadline.

Peeled like a grape

Hold your breath

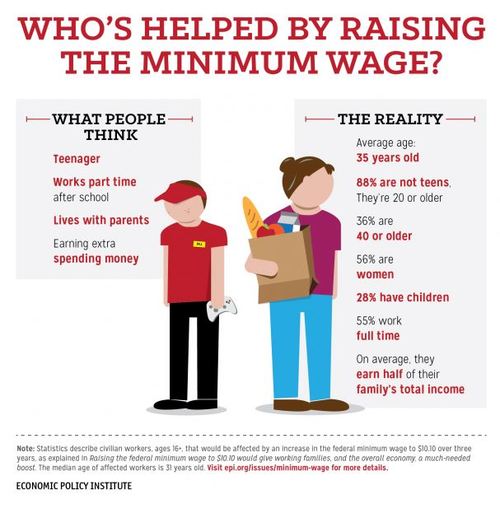

Know the facts

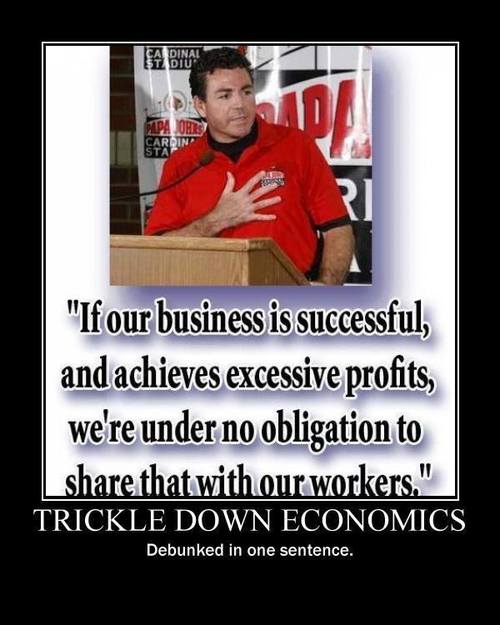

Trickle this

This is Papa John, here is a picture of his house. This is the guy who says he will cut hours so that no employees qualify for health insurance and then he doesn’t have to offer it. A corporate welfare King.